By KIM BELLARD

As you may have heard, the federal government is currently shut down, although for many federal workers – those deemed “essential” – that just means they keep on working but don’t get paid (and, in fact, some might never get paid). The cause is the now-standard failure of Congress to pass a budget. As it often does in these instances, the House did pass a continuing resolution (CR) to keep the government open (for seven weeks), and Senate Republicans are willing to go along, but Senate Democrats are balking. Even though they’re usually the ones who advocate “clean’ CRs, this time they’re holding out to include some other legislative fixes. Their key demand: continuing the expanded ACA premium tax credits.

I am a little puzzled why this is the hill upon which they’re willing to keep the government shut down.

Let’s back up. When ACA was passed in 2010, a crucial component was subsidies to help low- income people afford ACA coverage (along with subsidies for cost-sharing features like deductibles). Subsidies were, and are, crucial for the ACA marketplace to survive. These subsidies came in the form of premium tax credits.

If you recall the dismal individual health insurance marketplace pre-ACA, individuals couldn’t get coverage unless they passed medical underwriting, and, even then, preexisting conditions exclusions applied. As a result, few qualified and everyone complained. ACA did away with medical underwriting and pre-existing conditions exclusions, but the only way to ensure that enough healthy people would join the risk pool was to generously subsidize their coverage, much as employers do with employment-based health insurance. Thus the premium tax credits.

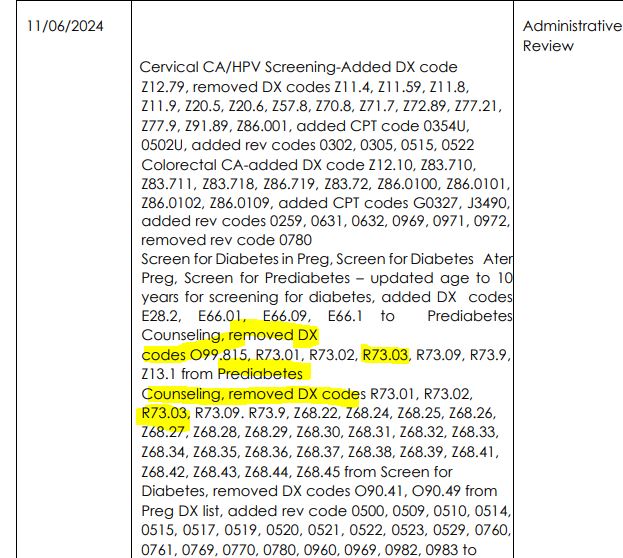

The trade-off worked for almost ten years. About ten million people got coverage through the exchanges. Then the pandemic hit. People needed coverage more than ever, yet many people’s incomes crashed. So in 2021 Congress passed “enhanced” premium tax credits as part of the American Rescue plan Act. They increased the amounts of the credits and made them available to some higher income families. Those expanded credits were extended to the end of 2025 as part of the Inflation Reduction Act.

It is those expanded premium tax credits that are expiring. The original credits would remain. Things would go back to the way they were pre-pandemic (although, of course, premiums are now higher due to inflation). It’d be more of a setback than a catastrophe.

The expanded tax credits did have a dramatic impact. Enrollment went from about ten million to over 24 million – 22 million of whom had the expanded credits. So it certainly is a non-trivial matter if they expire. KFF estimates that average premiums would double in 2026.

Still, though, CBO estimates loss of the expanded credits would result in about 3.8 million people losing coverage, which is a far cry from the 14 million whom gained coverage since they were implemented.

I’m not sure if the CBO is being overly optimistic, or if ACA has taught people to appreciate their coverage.

Everyone in Congress knew, or should have known, that these tax credits were expiring this year.

Continue reading…