I met the Nabla management team two years ago. Two years later they have ridden the wave of AI scribing to be one of the leaders in the field. At HLTH this year, I caught up with CEO Alex Lebrun and COO Delphine Groll to check in on their growth (150 customers and 100K users) what the next little bit of ambient AI scribing will look like (more specialties, more integration) and whether they’re scared of Epic (no!).–Matthew Holt

Struggling UnitedHealth Group is a Huge Smoking Black Box

By JEFF GOLDSMITH

In mid-April 2025, UnitedHealth Group (UNH) reported its 1Q25 operating results, including a modest shortfall in expected earnings and lowered its 2025 earnings forecast by 12%. The company blamed accelerating medical costs and federal policy changes for their most profitable service line, Medicare Advantage. Market reaction was swift and savage. UNH stock lost more than 22% in a single day. In May, United fired its CEO, Sir Andrew Witty and withdrew its earnings guidance for 2025, with the stock declining another 15%. Witty was followed out the door two months later by President and CFO John Rex, heir-apparent to longtime Chairman Stephen Hemsley.

Turns out, UNH’s market capitalization trajectory presaged the collapse in UNH’s 2025 cashflow. UNH’s projected cashflow from operations is now expected fall to be half of its 2025 forecast- a breathtaking $16 billion shortfall. In multiple investor calls, the new/old CEO Stephen Hemsley and his new crew have not come remotely close to explaining where the $16 billion went. Struggling UnitedHealth Group is one gigantic smoking black box.

2024 was a nightmare year for the company, beginning with the massive Change Healthcare cyberattack in February and concluding with the brutal killing of their senior health insurance executive, Brian Thompson, in November. It is clear in hindsight that business fundamentals for UNH’s health insurance and care delivery businesses deteriorated sharply during 2024, and its senior leadership were scrambling to repair the damage.

Health insurers across the country are experiencing record operating challenges. However, UNH’s business model enhanced their vulnerability. UNH had spent $118 billion in just five years (2019-2023) buying profitable smaller companies, almost all of which ended up inside of their enormous Optum subsidiary. These acquisitions included: multi-specialty physician groups, ambulatory surgery and urgent care, business intelligence/business process outsourcing and claims management companies.

These businesses are closely intertwined with United’s legacy health insurance business. In order to reach estimated $445 billion in total 2025 UNH revenues, one has to eliminate $165 billion in intercompany revenue flows (Examples- purchases of services by Optum Health from its consulting arm, OptumInsight, or purchase of health services from Optum Health by United Healthcare, UNH’s insurance business).

The company’s nearly fifty year old health insurance business had been a reliable 5.5-6% operating margin generator. However, in 2025, it will produce only a 3% operating margin. However, UNH’s incremental revenues and earnings growth for the past decade have not come from health insurance, but have been produced by Optum, whose revenues were growing much faster than its health insurance business.

Several pieces of Optum have also been far more profitable than United Healthcare itself. Optum Health grew into a $100 billion business (before eliminations), and used to earn an 10% operating margin. In 2025, that margin will be more like 2.5%. Optum Insight, a $19 billion business (before eliminations), which used to earn a sizzling 28% operating margin will be lucky to earn 8% in 2025. The complex interpenetration of Optum and United Healthcare’s businesses makes it impossible to gauge the seriousness of the company’s operating problems.

Optum Health appears to be a major source of the smoke, but it is impossible to tell from the skimpy disclosures where exactly the fire is.

Continue reading…Support your neighborhood scientist

By KIM BELLARD

These are, it must be said, grim times for American science. Between the Trump budget cuts, the Trump attacks on leading research universities, and the normalization of misinformation/ disinformation, scientists are losing their jobs, fleeing to other countries, or just trying to keep their heads down in hopes of being able to just, you know, keep doing science.

But some scientists are fighting back, and more power to them. Literally.

Lest you think I’m being Chicken Little, warning prematurely that the sky is falling, there continue to be warning signs. Virginia Gewin, writing in Nature, reports Insiders warn how dismantling federal agencies could put science at risk. A former EPA official told her: “It’s not just EPA. Science is being destroyed across many agencies.” Even worse, one former official warned: “Now they are starting to proffer misinformation and putting a government seal on it.”

A third researcher added: “The damage to the next generation of scientists is what I worry the most about. I’ve been advising students to look for other jobs.”

It’s not just that students are looking for jobs outside of the government. Katrina Northrop and Rudy Lu write in The Washington Post about the brain drain going to China. “Over the past decade,” they say, “there has been a rush of scholars — many with some family connection to China — moving across the Pacific, drawn by Beijing’s full-throttle drive to become a scientific superpower.” They cite 50 tenure track scholars of Chinese descent who have left U.S. universities for China. Most are in STEM fields.

“The U.S. is increasingly skeptical of science — whether it’s climate, health or other areas,” Jimmy Goodrich, an expert on Chinese science and technology at theUniversity of California Institute on Global Conflict and Cooperation, told them. “While in China, science is being embraced as a key solution to move the country forward into the future.”

They note how four years ago the U.S. spent four times as much in R&D than China, whereas now the spending is basically even, at best.

I keep in mind the warning of Dan Wang, a research fellow at Stanford’s Hoover Institution:

Think about it this way: China is an engineering state, which treats construction projects and technological primacy as the solution to all of its problems, whereas the United States is a lawyerly society, obsessed with protecting wealth by making rules rather than producing material goods.

We’ve seen what a government of lawyers does, creating laws and regulations that protect big corporations and the ultra-rich, while making everything so complex that, voila, more lawyers are needed. Maybe it’s time to see what a government of scientists could do.

Continue reading…A Failure to Rescue: How Predictive Modeling Can Rewrite the Story of Congenital Syphilis

By KAYLA KELLY

Every semester I have the privilege of guiding nursing students through their maternal and pediatric clinicals. At the beginning of the semester, their enthusiasm is contagious. They share stories about witnessing their first delivery, helping a new mother with breastfeeding, and practicing developmental assessments on pediatric patients. As the semester progresses, I see their demeanor shift. “You were right, we took care of another congenital syphilis baby today.” Their reflections on the clinical day are a mixture of emotions: frustration, anger, and sadness, as they watch fragile infants fighting an infection that no child should ever have to endure.

When I first tell my nursing students that they will likely care for infants born with syphilis during their clinical rotations, they look at me with wide-eyed disbelief. “Didn’t we cure syphilis in the 1950’s?” some ask. A few of my students usually recall hearing about the Tuskegee Study, but most have no idea that we are still fighting (and losing) a battle against congenital syphilis in the United States today.

Congenital syphilis occurs when a mother transmits the infection to her infant during pregnancy or delivery. It is almost entirely preventable with timely screening and treatment, yet the number of cases continues to rise at an alarming rate. Between 2018 and 2022, the United States experienced a 183% increase in congenital syphilis cases, rising from 1,328 cases to 3,769. This national trend was mirrored at the state level, with Texas reporting 179 cases in 2017 and 922 in 2022. During those five years, the rate of infants born with congenital syphilis in Texas rose from 46.9 to 236.6 per 100,000 live births, a sharp increase that necessitates action.

Texas now has one of the highest congenital syphilis rates in the country, despite having one of the most comprehensive prenatal screening laws. According to the Texas Department of State Health Services, policy mandates syphilis screening at three points during pregnancy:

(1) at the first prenatal visit

(2) the third trimester (but no earlier than 28 weeks)

(3) at delivery

But herein lies the problem: What happens when a woman never attends prenatal care? How do we reach those who never step into an OB/GYN office during pregnancy? Screening laws only protect those who are able to access care. In 2022, over 1/3 of Texas mothers whose infants were diagnosed with congenital syphilis did not receive any prenatal care. Each of these cases represents a failure of our current medical system, a system that should be protecting the most vulnerable yet remains unable to reach those who need it most.

Continue reading…When Your Cloud Provider Doesn’t Understand HIPAA: A Cautionary Tale

By JACOB REIDER & JODI DANIEL

Jacob: I recently needed to sign a Business Associate Agreement (BAA) with one of the large hosting providers for a new health IT project. What should have been straightforward turned into a multi-week educational exercise about basic HIPAA compliance. And when I say “basic,” I mean really basic, like the definitions in the statute itself.

Here’s what happened and why you need to watch out for this if you’re building health care technology.

I’m building a system that automates clinical data extraction for research studies. Like any responsible health care tech company, I need HIPAA-compliant infrastructure. The company (I’ll call them Hosting Company or HC) is good technically, and they’re hosting our development environment, so I signed up for their enhanced support plan (which they require before they’ll even consider a BAA) and requested their standard agreement.

The Problem

HC’s BAA assumes every customer is a “Covered Entity.” That means a health plan, a health care clearinghouse, or a health care provider that transmits health information electronically.

But that’s not me. I’m not a Covered Entity. I’m a Business Associate (BA). I handle protected health information on behalf of Covered Entities. When I need cloud infrastructure, I need my vendors to sign subcontractor BAAs with me.

The Back and Forth

When I told HC that I couldn’t sign their BAA as written, they escalated to their legal department. Days later, a team lead came back with this response:

“To HC, even if you are a subcontracted or a down the line subcontracted association. It would still be an agreement between the covered entity within the agreement and HC… So even being a business associate, it would still be considered a covered entity since it is your business that is being covered.”

I had to read it twice. This is simply wrong.

Jodi: Let me chime in here with the legal perspective, because this confusion is more common than it should be.

The terms “Covered Entity” and “Business Associate” aren’t interchangeable marketing terms. They have specific legal definitions in 45 CFR § 160.103. You can’t just redefine them because it’s administratively convenient. Generally… covered entities are (most) health care providers, health plans, and health care clearinghouses; business associates are those entities that have access to protected health information to perform services on behalf of covered entities; and subcontractors are persons to whom a business associate delegates a function, activity, or service.

Here’s what the regulations actually say:

Continue reading…Sachin Jain–How do we do better?

What are the practices that we have normalized that future generations will criticize us for? Sachin Jain, CEO of SCAN Health Plan, is perhaps the leading truth teller in health care who also runs a real health care organization. I had a really fun but serious interview with Sachin about what health care people are doing, what are the bad things that happen. How are good people letting this happen? How we should be changing what we are doing?–Matthew Holt

Hospitals are Incompetent Monopolists!

By JEFF GOLDSMITH

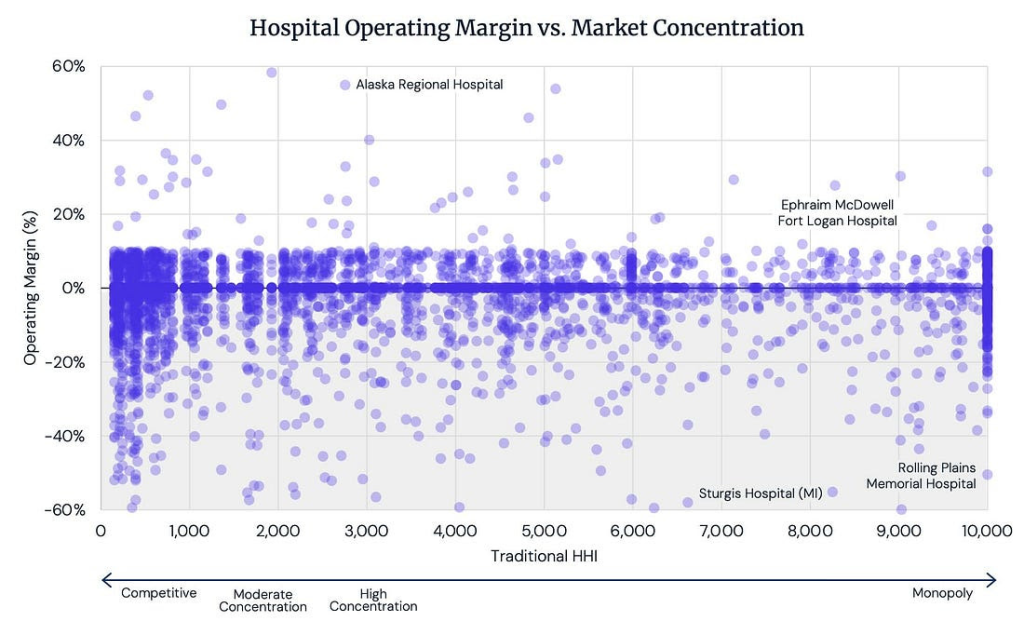

The health policy community is obsessed with hospital mergers. In a recent paper which I critiqued, the operating thesis was that hospital mergers are conspiracies in restraint of trade, enabling hospitals to extract rent from helpless local employers and patients. This logic leads directly to advocacy (lavishly funded by Arnold Ventures philanthropy) of hospital rate controls as the only way of restraining this abuse of economic power.

The reality is, as you might expect, somewhat different. The following chart, courtesy of healthcare data firm Trilliant Health, shows that hospitals are truly incompetent monopolists. It shows the correlation between hospital operating margins and market concentration for 2023. The hospitals to the far right in this chart have 100% local market shares.

Source: Trilliant Healthcare Analysis of CMS HCRIS files (Hospital Cost Reports), 2023

Do you see a correlation? I sure don’t.

According to Trilliant, the average hospital operating margin in 336 CBSAs (markets) where hospital services are “controlled by a single firm” is -1.7%.This negative operating margin average does NOT include the operating losses on their physician practices, which are not reported on hospital cost reports, so the actual operating losses are likely much greater.

Jeff Goldsmith is a veteran health care futurist, President of Health Futures Inc and regular THCB Contributor. This comes from his personal substack

Kai Romero, Evidently

Kai Romero is Head of Clinical Success at Evidently. The company is one of many that are using AI to dive into the EMR and extract data to deliver it to clinicians. It works to get really great information from the EMR to various flavors of clinicians in a fast and innovative way. Kai leads me on a detailed exploration of how the technology gets used as a layer over the EMR. And Kai shows me the new version that allows and LLM to deliver immediate answers from the data. This is a demo you really need to see to understand how AI is changing, and improving, that clinical experience. Meanwhile Kai is fascinating. She was an ER doc who became a specialist in hospice. We didn’t get into that too much, but you can tell about her input into Evidently’s design — Matthew Holt

Life Is Geometry

By KIM BELLARD

In 2025, we’ve got DNA all figured out, right? It’s been over fifty years since Crick and Watson (and Franklin) discovered the double helix structure. We know that permutations of just four chemical bases (A, C, T, and G) allow the vast genetic complexity and diversity in the world. We’ve done the Humam Genome Project. We can edit DNA using CRISPR. Heck, we’re even working on synthetic DNA. We’re busy finding other uses for DNA, like computing, storage, or robots. Yep, we’re on top of DNA.

Not so fast. Researchers at Northwestern University say we’ve been missing something: a geometric code embedded in genomes that helps cells store and process information. It’s not just combinations of chemical bases that make DNA work; there is also a “geometric language” going on, one that we weren’t hearing.

Wait, what?

The research – Geometrically Encoded Positioning of Introns, Intergenic Segments, and Exons in the Human Genome – was led by Professor Vadim Backman, Sachs Family Professor of Biomedical Engineering and Medicine at Northwestern’s McCormick School of Engineering, and director of its Center for Physical Genomics and Engineering. The new research indicates, he says, that: “Rather than a predetermined script based on fixed genetic instruction sets, we humans are living, breathing computational systems that have been evolving in complexity and power for millions of years.”

The Northwestern press release elaborates:

The geometric code is the blueprint for how DNA forms nanoscale packing domains that create physical “memory nodes” — functional units that store and stabilize transcriptional states. In essence, it allows the genome to operate as a living computational system, adapting gene usage based on cellular history. These memory nodes are not random; geometry appears to have been selected over millions of years to optimize enzyme access, embedding biological computation directly into physical structure.

Somehow I don’t think Crick and Watson saw that coming, much less either Euclid or John von Neumann.

Coauthor Igal Szleifer, Christina Enroth-Cugell Professor of Biomedical Engineering at the McCormick School of Engineering, adds: “We are learning to read and write the language of cellular memories. These ‘memory nodes’ are living physical objects resembling microprocessors. They have precise rules based on their physical, chemical, and biological properties that encode cell behavior.”

“Living, breathing computational systems”? “Microprocessors”? This is DNA computing at a new level.

The study suggests that evolution came about not just by finding new combinations of DNA but also from new ways to fold it, using those physical structures to store genetic information. Indeed, one of the researchers’ hypothesis is that development of the geometric code helped lead to the explosion of body types witnessed in the Cambrian Explosion, when life went from simple single and multicellular organisms to a vast array of life forms.

Coauthor Kyle MacQuarrie, assistant professor of pediatrics at the Feinberg School of Medicine, points out that we shouldn’t be surprised it took this long to realize the geometric code: “We’ve spent 70 years learning to read the genetic code. Understanding this new geometric code became possible only through recent advances in globally-unique imaging, modeling, and computational science—developed right here at Northwestern.” (Nice extra plug there for Northwestern, Dr. MacQuarrie.)

Coauthor Luay Almassalha, also from the Feinberg School of Medicine, notes: “While the genetic code is much like the words in a dictionary, the newly discovered ‘geometric code’ turns words into a living language that all our cells speak. Pairing the words (genetic code) and the language (geometric code) may enable the ability to finally read and write cellular memory.”

I love the distinction between the words and the actual language. We’ve been using a dictionary and not realizing we need a phrase book.

Continue reading…Waiting for Codman: 100+ Years of Profits > Patients

By LEONARD D’AVOLIO

I’m in the waiting room of the New England Baptist Hospital. They just wheeled my father to the OR. It’s strange to be back.

Once upon a time, their Chief Medical Officer, Dr. Scott Tromanhauser asked for my help. He was interested in improving the outcomes of total knee replacement surgeries. Nearly 20% of all knee replacements do not improve outcomes. The greatest opportunity for improvement is reducing unnecessary surgeries.

This seems straightforward enough to the casual reader but in the upside down that is US healthcare, very few surgical centers in this country bother to learn if their surgeries make things better or worse. Doing anything that threatens to reduce volume is bad for business.

We pitched a concept to his Board of Directors.

“What if,” we proposed, “we could measure 1 year post-operative outcomes of every total knee replacement? We could share that data with our surgeons and see – for the first time – how our patients fared. With enough data, we could make personalized predictions of outcomes during a pre-operative consult visit. We could give people the information they need to make good medical decisions.”

They supported the idea. Yes, it might lead to fewer surgeries – but these were the surgeries that shouldn’t be conducted. Plus, it might be an edge during price negotiations with payors. Beyond that, they concurred, it was the right thing to do.

Scott and I celebrated the approval with a walk through the Mount Auburn Cemetery to visit the grave of Dr. Ernest Codman. It was his idea after all.

Dr. Codman, was a surgeon at Mass General Hospital in 1905 when introduced his “End Results System.” In it, he proposed that every hospital capture data before, and for at least one year, after every procedure. This was to find out if the procedure was a success and if not, to ask “why not?” Codman wanted patients to have this information. How else would outcomes improve? How else would patients make good medical decisions?

Now, more than 100 years later, we would bring his idea to life, just miles down the road from where he introduced it.

Continue reading…