By JEFF GOLDSMITH

In the first part of our look at Arnold Ventures, we explored its business model and generous support of elite University health policy experts to further an ambitious health policy agenda. In this second part, we will explore some of the questions raised by Arnold’s aggressive approach.

Zack Cooper is an Associate Professor of Economics and Health Policy at Yale University*. He is the academic investigator at the heart of the so-called the 1% Solution, an Arnold Ventures funded project which encompasses most of its health policy agenda. The core idea of the “1% solution” is that while comprehensive health reform (e.g. “Medicare for All”) may not be achievable, pursuit of a bevy of policy goals with smaller price tags could generate savings that could be reinvested in policy improvements.

Cooper was the object of unwanted press scrutiny for receiving extensive sub rosa funding from United Healthcare for research work and writing instrumental in the enactment of the No Surprises Act in 2021, which was aimed at controlling out-of-network health insurance billing. United was expected to be the largest single beneficiary of this legislation. (The biggest “surprise” emerging from the No Surprises Act was that providers are winning 80% or more of the independent mediations of these disputes, suggesting that it was health insurers, not providers, who were gouging the public).

According to Arnold’s 990s, Cooper and his Yale policy shop, the Tobin Center for Economic Policy, received over $5 million from 2018 to 2024. Of this amount, $700 thousand funded the 1% Project itself, including more than a dozen papers by academic colleagues on topics ranging from surprise billing to PBM reforms to site neutral outpatient payment to hospital market concentration.

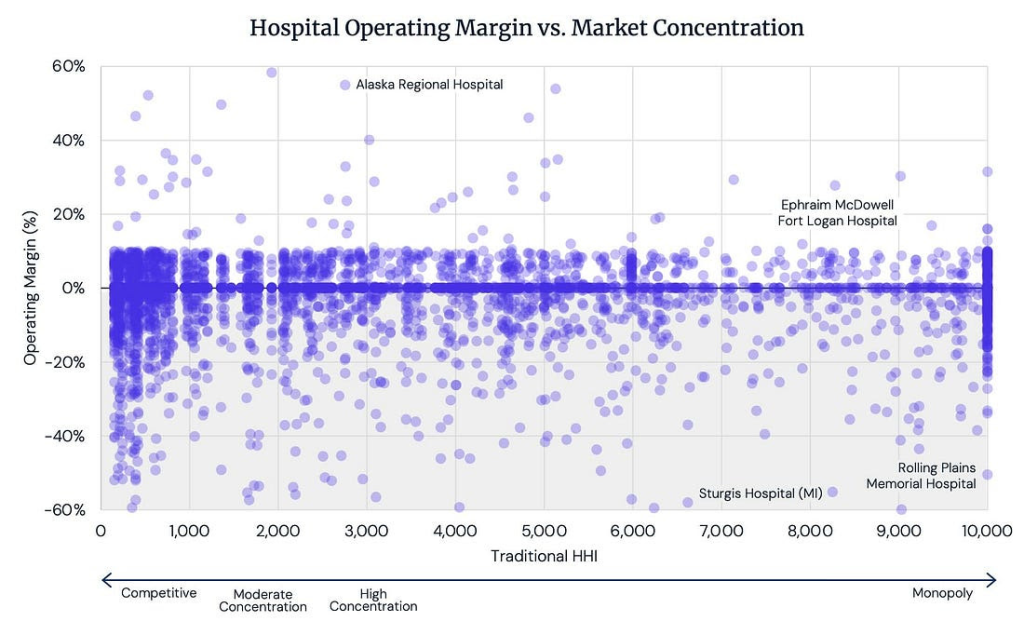

As part of this project, Cooper and a University of Chicago colleague, Zarek Brot-Goldberg, published a paper in early 2024 of the economic impact of hospital mergers: “Is There Too little Anti-trust Enforcement in the Hospital Sector?” which found that 20% of hospital mergers had an adverse economic impact on their communities. The alternative off-message headline, “80% of hospital mergers had no adverse economic on their communities” never surfaced.

However, a follow on piece got wide circulation thanks to a June, 2024 Wall Street Journal article, which exposed it to millions of readers without any reference to Arnold Ventures funding. The paper, which featured an astonishingly complex multivariate econometric model, was originally published by the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER is also funded by Arnold Ventures). This paper linked hospital mergers to widespread layoffs in the communities where the mergers took place and a subsequent wave of suicides and drug overdoses (!).

Continue reading…